Words by Gavin McClurg, Photographs by Jody MacDonald for Eddie Bauer

I feel like I’ve been chewing on cotton. My lips are cracked, my hips are sore, and I look again to the east, hoping for the grayness of dawn to arrive.

We had no food and our only jug of water had been contaminated with saltwater and sand. I was huddled down with seven other people in a makeshift bed made of two tandem paragliders. The fabric became an alarm clock every time we were blasted by wind or when one of us struggled to find a new spot on their body to relieve from the hard sand.

If I’d had a watch I’d have checked it for the thousandth time. The blanket of night refused to lift. I tried not to think about water and cussed silently to myself for orchestrating this mess. My body begged for sleep but my mind stammered off again, reconstructing how we ended up here.

We were marooned on a large island called Bazaruto off the coast of Mozambique. Our catamaran named Discovery, of which I am captain, was anchored several miles away. It might as well have been on Mars for the distance cannot be crossed. Our chef was the only one on board. He knew we were out here, but there was nothing he could do. A few hours ago all of us had been soaring – paragliding in a place that had never been flown before. We have been traveling the world by sail on a kiteboarding expedition since 2006, but we are also pilots and we’d come to Mozambique in search of airtime. Of all the discoveries we’ve made, of all the virgin playgrounds we’ve found over the years this one easily topped them all. But this seemed little solace right now.

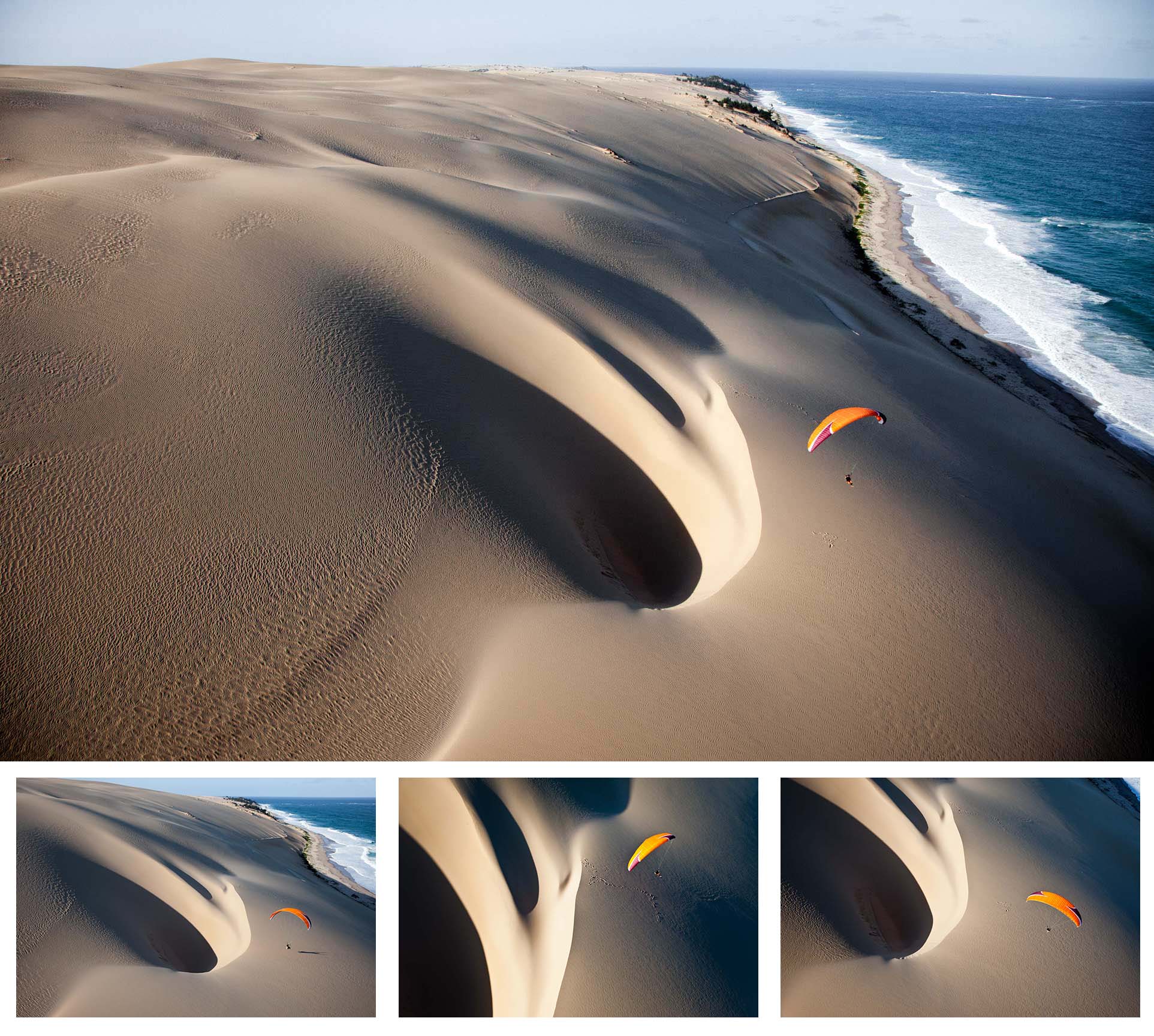

We’d seen this dune on a previous visit to the archipelago earlier this year. Checks on Paragliding Earth and the forums confirmed it was virgin territory. The dune stretches north to south nearly 30km, sloping up a few hundred metres from the tropical green Indian Ocean at an angle that practically screams to be flown, and is as impressive on sight as the more famous dunes of Namibia. A light breeze will keep you in the air forever, in fact it is possibly the most playful and beautiful soaring site on the planet, and certainly the best I’ve ever seen. No helmet or shoes required. But to get to it you have only two options. The first is to simply luxuriate at the gorgeous Indigo Bay resort, drive to the west side of the dune and walk to the top, which in total takes about 10 minutes. Easy.

We’d seen this dune on a previous visit to the archipelago earlier this year. Checks on Paragliding Earth and the forums confirmed it was virgin territory. The dune stretches north to south nearly 30km, sloping up a few hundred metres from the tropical green Indian Ocean at an angle that practically screams to be flown, and is as impressive on sight as the more famous dunes of Namibia. A light breeze will keep you in the air forever, in fact it is possibly the most playful and beautiful soaring site on the planet, and certainly the best I’ve ever seen. No helmet or shoes required. But to get to it you have only two options. The first is to simply luxuriate at the gorgeous Indigo Bay resort, drive to the west side of the dune and walk to the top, which in total takes about 10 minutes. Easy.

The other way is to arrive by boat on the east side, but this is of course exposed and requires a solid dinghy and some tricky navigating. Getting to the beach without getting gear soaked or flipping the boat is often impossible. There is no protection from the swell and every time we’d tried in the past the conditions were too extreme to attempt a landing. Tides range nearly five metres at Springs, which further complicates the matter. At dead low tide an outer barrier reef blocks some of the swell, and it is only then that a landing is possible. But at high tide whatever swell is running smashes unrelentingly right into the dune, creating an impressive and dangerous shore break.

My mind returned to the present. At last there was a line of grey on the horizon. I couldn’t wait to escape the flimsy confines of this ‘bed’ and get my aching muscles moving. I was daydreaming of coffee and food, wondering if Ezra, our chef, was awake yet, prepping yet another gorgeous meal. If I hadn’t been so dehydrated I would have been salivating – he was an extraordinary chef and had blown all of us away for the previous 10 days. But we had to get there first.

Our dinghy was high-and-dry. It was not supposed to be. No one saw it land on the beach, but we knew it must have been a hell of a ride, thankfully un-manned. Twenty hours before I had anchored the dinghy well beyond the shorebreak, dived down to the bottom and wedged the anchor under a large rock and swum to shore. We’d dropped off all the gear and people earlier in the day at low tide when it was safe. The conditions were perfect for flying and we all raced to get in the air. As I launched I remember looking out at the dinghy thinking, Please let that anchor hold. The waves were well over two metres and hammering the beach with continuous fury. If the anchor slipped, our boat would likely not survive.

But the urge to fly was too great and my worry was quickly overtaken by the pure magic of flying this place. We had five pilots and two passengers in our group. Mike and Stu Belbas, who run Verbier-Summits Paragliding in the Swiss Alps, took turns flying solo and tandems; our good friend Bruce, a veteran kitesurfer and recent flying addict from Australia; myself and my partner Jody were all solo. We’d figured out how to put my first mate Tim hanging backwards on tandem so he could shoot video, while Leah and Rosie, more friends from Verbier, took to the skies whenever a tandem seat was available. We spent hours in the air screaming in delight like children in a sandbox. You can skim inches from the sand at ridiculous speeds, throw absurdly big wingovers, fly out over the ocean and return to take the dune elevator right back to the top… it is a site that had surpassed my wildest dreams. We flew miles down the dune away from our day camp as the shifting light of day turned the dune and ocean through a spectrum of colour that took our collective breath away. As sunset neared Jody was on tandem with Stu taking photos while Bruce and I tried to outdo each other’s best acrobatics.

Each of us was in a temporary state of bliss, we had entered another world; we had found Nirvana.

And then all of it was shattered by a few words. “Gavin, do you see the dinghy?” Jody and Stu were flying right next to me. The sun had set, we had been flying most of a day that none of us wanted to end. I hadn’t even thought about landing, I wanted to fly until I could not see. We were still a great distance from where the dinghy should be and I was hoping it was just the light that robbed us of the sighting. But in my gut I knew we were in trouble. A few minutes later I landed in the soft sand and sprinted to the beach. The tide was again retreating but the waves were massive. Nightfall was descending.

Somehow the dinghy was upright. It was filled with water to the gunnels, sitting lopsided like driftwood. A cushion and pump were missing, the battery was submerged, but the engine appeared undamaged. Maybe we were lucky? But there was no way to get the dinghy back out through the shorebreak, and there was no way to get back to Discovery without the dinghy, so we were staying put for a while.

I snapped back to the present. The dark was finally fading. It had been a very long night. The warmth of the sun was near. We were cold, thirsty, hungry and tired. The tide was still too high to try to get off the beach. There was an onshore breeze. Bruce and I grabbed our wings and launched, howling at the rising sun like mad wolves. Mike and Stu followed shortly after. We couldn’t eat or drink or go anywhere, so we might as well fly.

The pain of the night dissolved as soon as I was in the air. My blood circulated to my extremities and my brain began firing a soothing combination of endorphins and adrenaline and my hunger and thirst were quenched, if only temporarily. My mind wandered off again, to an earlier time on this trip while still back in Madagascar, 800km east across the Mozambique Channel. I overheard someone say how much older I looked these days. The stress of keeping this expedition alive all these years is exacting a toll, no doubt shortening my own time on this amazing planet in the same way drugs or alcohol do. I thought about one of my favourite quotes: “It’s not an adventure until something goes wrong.” In my experience, making discoveries like we had here in Mozambique always comes at a cost: physical, emotional and economic. But flying in Mozambique, along the Bazaruto dune? Priceless.